Published in Period! on 13th January 2025

www.period.media/quotes1/bashali-a-place-of-freedom

With the Kalasha people in northern Pakistan, menstruating women can choose to retreat to a bashali, a sacred space only for women on their period or about to give birth. Human rights lawyer Farah Ahamed reports on this place of personal reflection and collective wisdom.

The experience of menstruation, often laden with social stigma, takes on a different meaning when women have the freedom to choose how they spend this time. In the Kalasha culture of northern Pakistan, menstruating women are given the agency to retreat from their daily responsibilities and embrace a space dedicated to rest, reflection, and community. This autonomy during menstruation upholds the dignity of the experience, empowering women to honor their bodies and their needs without shame or restriction.

In the northwest region of Pakistan, the Kalasha people have thrived since the 11th century, living in the valleys of Bumburet, Birir, and Rumbur within Chitral District. This small community of around 3,000 people follows a unique cultural tradition where women are azat (free) and have chit (choice). They speak Kalasha, or Kalasha-mun, and live by customs that empower women to assert autonomy in their personal and community lives.

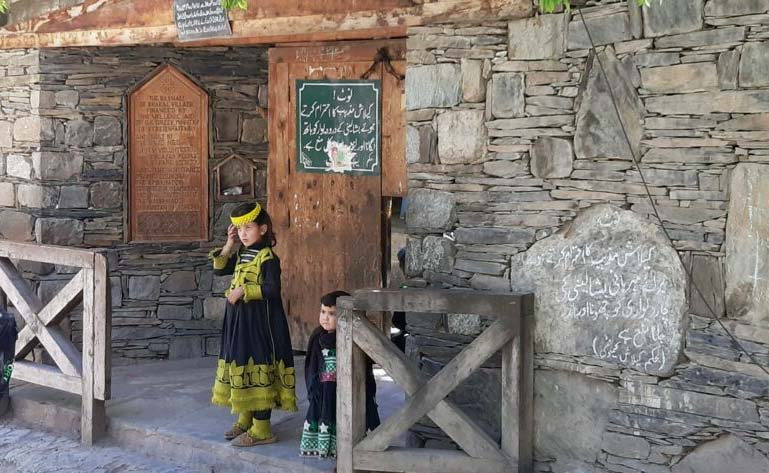

Bashali: a home for women during menstruation and childbirth

In these valleys, you will often encounter wooden signs directing you to the Bashali, or maternity home. Curious, I asked my guide about the bashali and was told it was a sacred space where Kalasha women went during menstruation and childbirth. I asked if I could visit, but he cautioned me that entry was strictly forbidden to outsiders – only menstruating women and those about to give birth could enter. Even female family members were prohibited from disturbing them. Men were never allowed to enter, touch the walls, or doors of the bashali. It was a private space curated exclusively for women.

By a stroke of luck, I was able to meet two local women – Rabia Kausar, an Observer at the Directorate of Labour and Bureau of Statistics, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Safina Safdar, a Third Party Field Monitor at the Health Department – who were willing to take me to visit a bashali. After explaining that I was writing a book on menstruation, they offered to act as interpreters and help me navigate the cultural intricacies of the Kalasha community. With their help, I was granted permission to visit the bashali and speak with the women there.

A peaceful bungalow nestled within a spacious compound

The bashali I visited in Bumburet was a peaceful bungalow nestled within a spacious compound. It was a self-contained space, complete with a porch, six beds in two rooms, a kitchen, a shower, toilets, and running water. The house exuded a calm atmosphere. Although the bashali may have looked quite different decades ago, today it resembled a modern hostel. The compound was surrounded by towering pines, deodar, oak, and chlghoza trees. Myriad birds, including mynas, fluttered in the branches, and a cat lazily sunbathed in the corner.

Inside, women relaxed and tended to their crafts. A woman embroidered a black skirt while chatting with a friend on a charpoy. Others prepared outfits and headdresses for the upcoming Chilam Joshi spring festival. The air was filled with laughter and camaraderie, and there was an undeniable sense of sisterhood. In one bedroom, two young women lay chatting, their voices punctuated by bursts of laughter. Nearby, a baby cot stood empty.

‘I come here every month (…) It’s a time of freedom’

Mazdana, a woman in her forties, explained the cultural significance of the bashali. ‘I come here every month during my period,’ she said. ‘It’s my time to rest from the demands of family and household chores. I don’t cook or carry heavy loads. Here, I sleep, chat with friends, and do embroidery. In the evenings, we sit together, share stories, sing, and dance. We do whatever we want, when we want. It’s a time of freedom.’

Mazdana continued: ‘We bring our own blankets, and every day, someone from our families leaves food outside the bashali. We can’t greet our families or speak to them during this time. The utensils for our meals are kept separate. We don’t bathe or change our clothes until our bleeding stops. It’s not about being impure, but about giving our bodies a break.’

Despite its restorative qualities, there were occasional inconveniences. During festivals or important occasions, women in the bashali were unable to socialize, and the cold winters made some reluctant to spend time in the space. Yet, for many, the bashali provided a much-needed respite from the pressures of family life.

Cornerstone of the Kalasha women’s community

Though menstruation is not viewed as shameful by the Kalasha, it carries a sense of separation and ritual purity. Rabia and Safina told me that, on days when menstruating women were inside the bashali, no one could enter their homes.

A fourteen-year-old girl, Ratumi, shared her understanding of menstruation. ‘My mother told me,’ she said. ‘When she gets her period, she goes to the bashali. Everyone knows about it. It’s part of our culture. When I first menstruated, my mother showed me how to use cloth. We don’t use store-bought pads. The bashali is like a second home, a place of freedom.’

The bashali is not merely a resting place; it is a cornerstone of the Kalasha women’s community. During their time there, women bond, exchange knowledge, and support one another through various life stages, including puberty, childbirth, and menopause. Safina explained that upon reaching puberty, girls undergo purification rituals and offerings to Dezalik, the goddess of fertility, childbirth, and womanhood. The first menstruation is marked by a ceremony before Dezalik’s statue, after which the girl’s initiation into the sisterhood is completed. The bashali serves as both a space for personal rest and a sanctuary for collective wisdom and solidarity.

Shared experiences

Inside the bashali, specific rituals are observed. Women must wash their hands before touching food, beds, or the floor. Shoes worn inside are never worn outside. The traditional headdress and beads are set aside, allowing women to relax and be unencumbered by societal expectations.

I witnessed firsthand the openness with which women talked about menstruation and childbirth. The bashali was a place of candid conversation, where women learned about their bodies and exchanged tips on everything from reproduction to traditional crafts. These shared experiences created a profound sense of connection and empowerment.

In Kalasha culture, all marriages are love marriages, and the bashali plays an important role in fostering the bonds between women. In their communal space, women share their lives, support one another, and, at times, engage in playful teasing and banter.

I asked Safina if women ever pretended to menstruate in order to escape to the bashali. She admitted that sometimes, women used menstruation as an excuse to escape domestic pressures or to delay returning home. Others sought refuge from unhappy or abusive marriages. The bashali thus serves as a space for personal reflection and freedom from societal constraints.

A place for solitude

The Kalasha practice of menstruation rituals invites a reconsideration of women’s bodily autonomy and privacy. As Rebecca Solnit notes in her essay Men Explain Things to Me, women often find their experiences and knowledge overshadowed by male authority. Solnit references Virginia Woolf, who once wrote about the deep freedom women might experience when allowed to exist solely for themselves, without external pressures or obligations.

Woolf’s insight into solitude (‘For now she need not think about anybody. She could be herself, by herself. And that was what now she often felt the need of – to think; well, not even to think. To be silent; to be alone. All the being and the doing, expansive, glittering, vocal, evaporated; and one shrunk, with a sense of solemnity, to being oneself, a wedge-shaped core of darkness, something invisible to others. Although she continued to knit, and sat upright, it was thus that she felt herself; and this self, having shed its attachments, was free for the strangest adventures…’) reflects the profound solitude and freedom Kalasha women experience in the bashali.

Reclaim freedom

The bashali offers Kalasha women the chance to reclaim their freedom, to retreat into a space of self-reflection, and to nurture both individual and collective identity. Here, they can be themselves, by themselves, free from external expectations, and unbound by the limitations often placed upon their bodies. The bashali serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of women’s agency and choice, offering a sanctuary where they can rest and reclaim control over their bodies and experiences in a world that too often seeks to regulate and control them.